Tania (00:10):

Hiya, I'm Tania, pronouns she/her.

Rudy (00:12):

And I'm Rudy, pronouns they/them.

Tania (00:16):

And we are from the Black Digital Archiving Project podcast. The project was created as a way to investigate the state of digital archives for and about Black people in the UK. As part of the podcast series, we have invited a number of guests whose work is relevant to those Black communities. Through the podcast series, we are going to cover a number of topics, including celebration, loss, migration, education, and resistance.

Rudy (00:43):

We're very happy today to welcome Kelly Foster, pronouns she/her, who is a public historian specialising in Black histories, social and women's history of London. She uses oral histories and archival research to deliver tools that delve into the social history of London's neighborhoods. Kelly has worked with community/independent archives in London for over 15 years and is a founding member of TRANSMISSION, a collective of archivists and historians of African descent. She's also an advocate in the open knowledge movement, and works to encourage more people of African heritage to contribute to Wikipedia and its sister projects. Thank you, Kelly. Welcome.

Kelly (01:36):

Thank you. Great to be here.

Rudy (01:38):

For those who may not be familiar, can you tell us a bit about what the London Blue Badge Guide is and how you became one?

Kelly (01:46):

It's essentially a qualification that allows you to take people around, to guide people in the likes of the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey, Windsor Castle. The major tourist attractions in London and anywhere that you can get to from London in one hour. And so it's an accreditation, a qualification, however you want to call it. And again, I don't necessarily think it means much to anybody outside of the tourism industry, but it's a qualification you get after a two year course, and you learn to guide in these places, with a view to be able to work in the tourist industry, the travel industry, in London.

Kelly (02:28):

I most enjoy doing work that looks at what I have quite lazily called "community histories" in London. So oftentimes that means the histories of the most marginalized people in this 2000 year old city. So this is leading walking tours, working in galleries and museums in London. So it's a qualification and not one that I use particularly often, but it is something that I have anyway.

Tania (02:55):

When we think about tourist attractions or tour guides, that is the thing that comes to people's minds. "Where was Harry Potter shot?" And "Ooh, the London Eye," and all of these different things. But I think what is really interesting is how you take the things that are important to you and use that as a learning tool for people who are visiting the city.

Tania (03:16):

So I just wanted you to talk a bit more about the importance of acknowledging and preserving, and also revisiting spaces that hold a cultural and historical significance to marginalized communities, but more specifically for people of African descent.

Kelly (03:30):

I'll talk a little bit about something that annoys me first of all. And that's the phrase, "Hidden histories." It's used less than it was 15 or 20 years ago, but it's still used as a shorthand to speak about histories and pasts that have been ignored and undervalued and dismissed, which are all adjectives that I prefer to use. And London's a 2000 year old city and there have been Africans in London for as long as there's been London. There are Africans, or people who've been racialized as Black, that are in the Roman cemeteries that were around the wall of the Roman city of London.

Kelly (04:15):

So being able to speak about those people over 2000 years, many of whose names we don't know, as well as the people that are more notable, whose histories, whose names, whose lives may be more familiar with, is incredibly important. One of the things that I really enjoyed doing... If I were to use the word practice, which I very rarely do, but if I were, what I try to do is to speak people's names, not only as an act of citation and recognition, but also as acts of remembrance as well.

Kelly (04:55):

So one of the tours that I do in Brixton, which is the neighborhood where I grew up, is about the geographies of the Black Power movement in Brixton in the late 60s and early 70s, and also of the Black women's movement in Brixton, also during the same period but in the early 80s as well. And being able to speak the names of women who quite often don't make it to the pages of books, whose activism and contributions are often undervalued, is an incredibly important thing to do. And this is why I use the term "public historian" when I speak about myself or when I speak about what I do. It's a knowledge that is embodied not only in the routes that we take, in the geographies and the footsteps that we're walking in, but also in, again, the names of organizations and of individuals that I encourage people to recall.

Rudy (05:53):

You have been involved in so many different things, which is amazing. I was wondering if you could just say a bit about how you got involved in working with archives, and maybe just a bit more in practical terms about how that came to be? And then also, if you could speak about your work with TRANSMISSION?

Kelly (06:18):

Around about 2004, I was working at the British Council, which calls itself "the cultural relations agency of the UK," but is really cultural imperialism from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. And a colleague of mine dragged me down to a meeting held on the corner of Coldharbour Lane and Atlantic Road in Brixton, at a shopfront that usually has its shutters up. And that was a meeting at the old home to the Black Cultural Archives on the corner of Coldharbour Lane, 378 Coldharbour Lane. And the meeting was being held because Black Cultural Archives was going through a significant transition and planning towards the next stage of its life, in trying to get a capital project off the ground and to create a building in Brixton that would be its new home when it moved from that corner, which is now the hip-hop chip shop on Coldharbour Lane, as I mentioned.

Kelly (07:19):

So my workmate dragged me along to this meeting and I sat in this meeting with various people. I'll mention a couple now. So there was Kate Theophilus, who's an arts administrator, and Marcus Ryder, who is a QC and lives locally in Brixton, and Jacine Garrison. And even though I had grown up in Brixton and I'd walked down Front Line holding my grandmother's hand or my grandmother's shopping trolley more times than I'd like to remember, I'd never really noticed this shop facade. I'd only noticed that they had a bookshop at the back.

Kelly (07:52):

From that meeting in 2004, I then went along to another meeting at Lambeth Town Hall where the cabinet of Lambeth was meeting to discuss making a contribution to this capital build, and the capacity building and feasibility studies and all of these reports or studies that would have to be done in order to open Black Cultural Archives. And it took 10 years for Black Cultural Archives to be reopened. It eventually was in 2014, in Brixton in Windrush Square, and that's still where the site is to this day.

Kelly (08:25):

And I worked at Black Cultural Archives first as a volunteer, invigilating and manning the exhibitions, helping plan some of the exhibitions. This was all under the leadership of Jacine Cooper, who was the niece of Len Garrison, one of the co-founders of Black Cultural Archives, or to give it its proper name, the African Peoples' Historical Monument Foundation. Not quite as catchy as Black Cultural Archives, a bit more than a mouthful, but an important thing for me to mark here and I'll tell you a little bit about why that is in a second.

Kelly (08:50):

So I went from being a volunteer at Black Cultural Archives to when they moved their temporary premises in Kennington, in Othello Close, ironically enough. I then started working there as they were transitioning from having one member of staff into bringing more people on staff. And I worked at Black Cultural Archives, or BCA, maybe till about 2012. And that is when I decided to retrain and be a Blue Badge Guide, which seemed like a good idea at the time. So that was really my first introduction into the "archive sector," in inverted commas, although Black Cultural Archives is very much unusual in the broader archive sector in the UK.

Kelly (09:28):

And then as I was working as a Blue Badge Guide, as I was beginning to ask and try to answer questions about the Brixton that my grandparents would have known when they came over in the early 1950s, questions about, "What is the story behind Windrush?" "How much of it is mythologized and how much of it is factual?" And I began to spend rather too much time in Lambeth archive, which is our local authority archives for the London Borough of Lambeth, and began to visit other local authority archives around London, to familiarize myself with the type of records that those types of archives have about Black people or about people that are racialized as Black.

Kelly (10:05):

Yeah, so began to use archives as a way of investigating and digging in ways that unveil stories and pasts that aren't always documented in books, and they definitely aren't documented in books that are easy to find. And it's not even a huge amount, but there are significantly more academic books about Black histories in the UK than there were 10, 15, definitely 20 years ago, about radical histories especially. Activist histories. So initially to find and dig through that, you had to be doing oral histories, you had to be working with archives. Black Cultural Archives has a really strong ephemera collection. So ephemera are the types of records that would otherwise be thrown away. So flyers, posters, tickets. That is really rich, and that gives a really interesting view of the spectrum of different community organizations and activities over the past 40 years.

Kelly (10:54):

Whilst at Black Cultural Archives, I would say one of the more significant projects that I was involved in... They're all significant, but one that I recognize as making an impact 10 years later, was a project that we did that collected 36 oral histories of women involved in the Black women's movement. And seeing the impact that that collection of oral histories has really transformed the scholarly landscape and what is published about Black women, their organizing, their activism, just their everyday lives.

Kelly (11:26):

So it went from volunteering in 2014, through to being one of the only two or three members of staff at Black Cultural Archives, through to this, I think £8,000,000 capital project. And that gave me an introduction into police records, colonial records, even the licensing record. There are very interesting things that you can pull out from, I guess the minutiae of what's often seen as being boring municipal records. Again, these records, they have nuggets of lives and celebrations that often haven't been recorded.

Tania (11:59):You mentioned the other name for the BCA, and you said you were going to talk a bit more about why that was important.

Kelly (12:05):

Yes. So, Black Cultural Archives is a project of the African Peoples' Historical Monument Foundation. There are several reasons why it's important, but I guess one of the most obvious ones is that the official name for Black Cultural Archives includes the word "African" and represents the Pan-African internationalist ambition that Black Cultural Archives had when it was established. Actually it's the African Peoples' Historical Monument Foundation UK. And that is because it's the UK branch of a broader organization, or the vision of a broader organization, that was established by a woman called Audley Moore, who is better known as Queen Mother Moore.

Kelly (12:48):

I think Queen Mother Moore was born in Louisiana in the 1890s. So she was born in the American South, essentially. And she migrates north in the great migration to Harlem, to New York, and her life in the 20th century follows the trajectory of Black liberation movements throughout the 20th century. So in the 1920s, she's active in the Universal Negro Improvement Association and she's active in the Garveyite movement. In the 1930s and 40s, she's active in the Communist Party of the United States of America, as anybody would be, if they're interested in equality, they were a communist in the 30s and 40s. In the 50s and 60s she's active in the civil rights movement, and come the later part of the 60s, she is now an elder and she is working in the Black Power movement, and I guess is most often spoken about today because of her involvement in the New African Republic and being one of the cornerstones of keeping the flame for reparations for slavery alive in the USA.

Kelly (13:46):

So in the late 1970s, she traveled over to the UK and she did a series of talks and lectures touring around the UK. I should say that tour was sponsored by a Rastafari organization called Tree of Life. And one of the people that heard her speak and that heard her advocate for a memorial to Africans that died as they were being trafficked across the Atlantic into slavery, was Len Garrison. And I think Queen Mother Moore's visit, not necessarily sparked but definitely kindled an archival impulse in the UK. And with her visits and other archival record of meeting minutes... And another reason why it's very important if you're in an organization, or you're organizing, to keep good records. An indication from the minutes of several types of organizations is that there was this archival impulse, and eventually they established the African Peoples' Historical Monument Foundation UK as a UK branch to meet Queen Mother Moore's aim of memorializing dispersed Africans, and also to create a monument to those who died in the Middle Passage.

Kelly (14:49):

So for me, the name brings up that whole internationalist context, this deeper link to the past, and is a recognition of the lineage of organizing for liberation of African and African-descended people. So that's why it's important to mention and to recognize not only the name of the organization but also Queen Mother Moore.

Rudy (15:14):

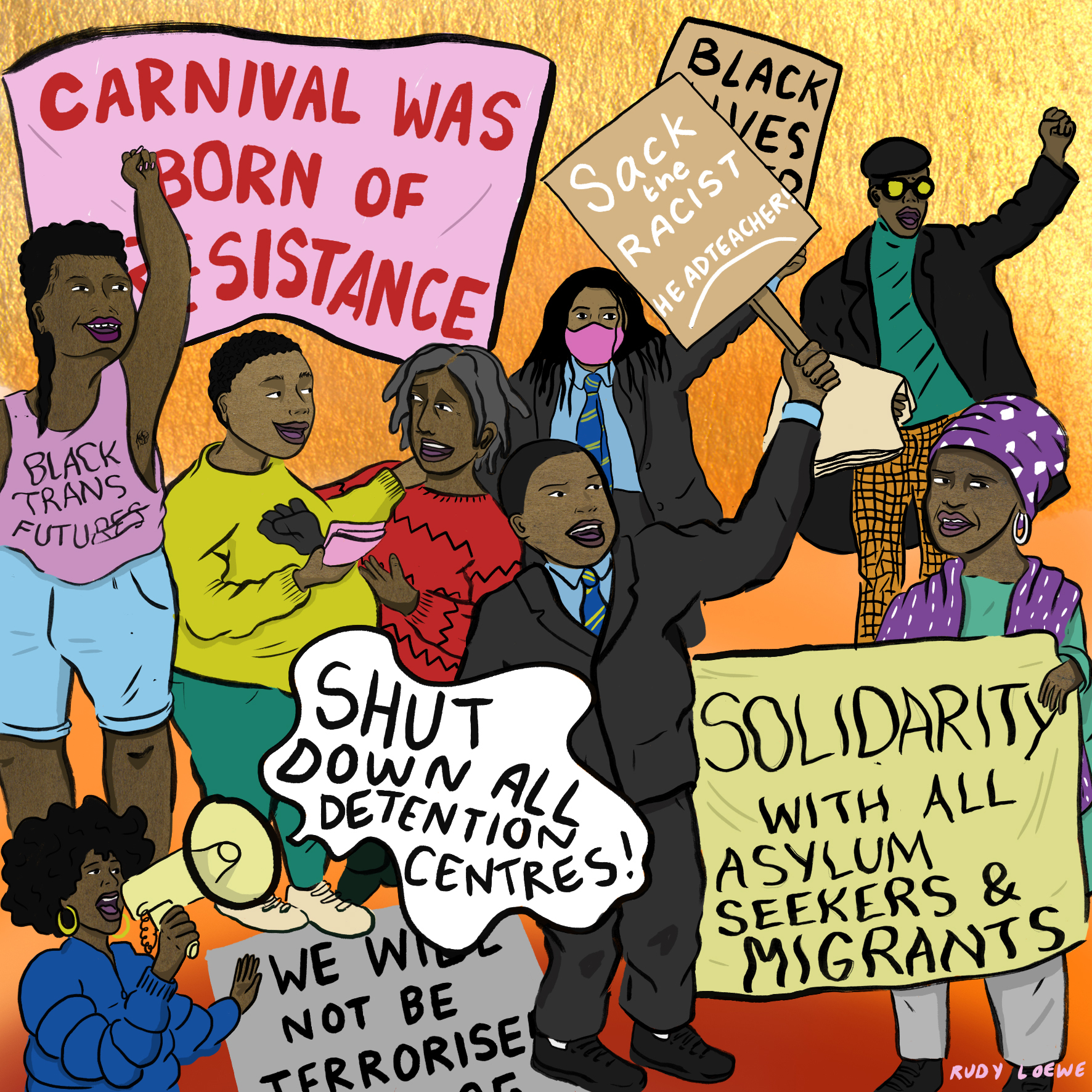

You touched upon how celebration features in the archive, and this was one of the themes that we were interested in discussing. How can we archive cultural celebration, and how can this be passed through the archives to a different generation?

Kelly (15:39):

So, I guess it's useful to think about what you mean by "archive". If archive is the preservation of memory, then the best way to archive celebration is through celebrating stuff. So that act of memorialization, festivals, parties, even the different tradition, different embodied ways of knowing, is an act of preservation and an act of archiving. But that is quite at odds with archiving as it's seen in the traditional sense, and traditionally that is mostly paper-based records, and I guess now it's more digital records as well.

Kelly (16:15):

So, thinking about what is archives and what is memory and thinking about Black Cultural Archives again, and Black Cultural Archives having a building... And one of the co-founders of Black Cultural Archives, a man called Len Garrison, who was really responsible for keeping the organization going and ensuring the sustainability of the organization, he wrote a poem called Where Are Our Monuments, in 2021. With the constant conversations about monuments going on in the public, I oftentimes think of the building and the activity that goes on within Black Cultural Archives as an important archive in and of itself, and as an important monument in and of itself, that goes away from memorialization being about individuals and being about the great and good and putting people on pedestals, and goes towards how do we memorialize and create an archive of collective action, of change-makers, that go beyond, in my opinion, an often flawed and narrow perspective that is based on an individual and their image?

Kelly (17:16):

So yeah, there are the conventional ways, through photography, through film, through good record-keeping, because celebrations take organizing as well and it's important to keep records about that organizing. But fundamentally it's through participating and remembering through participation.

Kelly (17:34):

The 1st of August is Emancipation Day in the parts of the British Empire, apart from India, where enslavement was abolished in 1838. And it's only really since there has been a Stop the Ma’angamizi march on Emancipation Day, a Reparations March, as it's called. It's only really since that has been marked in the UK, I think it was the fifth year last year, that there has been a growing recognition of the importance of Emancipation Day. In the Caribbean, Emancipation Day as a public holiday used to be marked, back in the post-abolition period in the 1830s and 40s. But by the time independence came around in the 1960s, Emancipation Day as a public holiday was replaced by independent days, and only really over the past 20 years or so has Emancipation Day been a public holiday, especially in Trinidad and Jamaica. As I mentioned, in Barbados it's part of emancipation season. As an act of further shaking off the colonial calendar, for want of a better word, and putting in the official calendar celebrations or commemorations that were important and significant to African people.

Kelly (18:51):

So how do we remember Emancipation Day on the 1st of August? And even in our flawed and narrow way that we remember Emancipation Day, for me, the most useful way to remember it is to go to the Reparations March that's held in London, is to participate in one of the Emancipation Day events that are held all around the country. That to me is one of the more useful acts of archiving and remembrance.

Tania (19:22):

I think, for things like Emancipation Day, not a lot of people know about it and why it's significant. And I was just wondering... I don't know if this ties into your work with crowdsourced information sites and things like that, and why that's important for people of the diaspora to be empowered with those skills, to be able to document the things that are important and why they're important also?

Kelly (19:48):

So, I grew up mostly in my grandmother's household and my grandparents came to the UK in the early 1950s, and they were already a bit older than most of the people coming in here during that period. And my parents were born in the late 1950s post-war, and they were an early post-Windrush generation that was born in the UK. They were not the first. So I grew up in a very Jamaican household and both my grandparents had been children, or young people at least, in the 1930s when there were significant labor rebellions in the Caribbean because of the exploitation and continuation of imperialism that was happening there, but specifically because of the exploitation of the major sugar corporations at that time.

Kelly (20:31):

So the household that I grew up in, I remember it as having a lot of political awareness. I don't know necessarily whether my grandparents would have identified as being Garveyites or as being Pan-African, but they definitely were not apologetic, or they definitely didn't shy away from acknowledging that they were African. And they were in the UK when Jamaica became independent in 1962. And at that time of independence, a lot of Jamaican people had souvenirs of independence up on their wall. So you'll find a map of Jamaica, or there was a scroll with the coat of arms and the motto of the country and the Act of Independence as well, printed on there.

Kelly (21:14):

My auntie had gone to live in the States in the early 1960s, and she would send over African-American magazines and books occasionally. There was a great big carpet portrait of Martin Luther King on the dining room wall. A carpet portrait is a very interesting thing, but there was one of those. There were posters of the Jamaican national heroes in the house as well. And also I grew up with uncles in my granny's house who in the 1990s were active in and interested in the, I guess, African consciousness movement in the 1990s as well.

Kelly (21:49):

So there were always publications around the house. There were always conversations in the house about Black history, about African history. And there were always my grandparents talking about the past as well. So that was something that was constant in the household that I grew up in. So I'm always a little bit shocked, I guess, for people who didn't have that foundation in their life, where they were talking about these kind of broader internationalist issues, whether it be apartheid in South Africa, or whoever the newest prime minister is in the Caribbean, or anti-Africanness in the Caribbean. So that was always an important foundation and important fuel for me.

Kelly (22:29):

So to go on to the working with Wikipedia and its sister projects, I was introduced to that when I went along to an edit-a-thon, which is a workshop where you learn how to edit Wikipedia, in 2012. I know the precise date because there's photographic evidence. And I think this may have been the first Black History Month Wikipedia edit-a-thon that happened, perhaps just in the UK but maybe globally, in October of 2012. And it was hosted by an organization called the Equiano Center. The Equiano Center, again, that's cool names. The Equiano Center was hosted by University College London, but the founder of that was a young academic called Caroline Bressey, who is a geographer and still is in the geography department at UCL. And another key organizer is a historian and incredibly influential writer in my life, Dr. Gemma Romain. So Caroline and Gemma ran the Equiano Center, and I think were really pioneers in working with digital mapping and blogs and what was then called Web 2.0, in making London Black histories more visible online.

Kelly (23:33):

One of the trainers there was a man called Fabian Tompsett. And Fabian I knew from Black Cultural Archives, because he was a key figure in BASA, the Black and Asian Studies Association, B-A-S-A. And I got to know Fabian and he taught me how to edit Wikipedia, and then a light bulb moment went on there in the workshop, because when you spend a lot of time on Wikipedia, you realize where all the gaps are, you realize where the biases are, you realize where the omissions are. But that first time that I started to edit Wikipedia, I learned how to edit but I didn't really go back to it for a couple of years because that was still peak raving days and I had better things to do.

Kelly (24:13):

So it wasn't for a couple of years. And then I went along to the No Color Bar exhibition that was at Guildhall Gallery. And this was an art exhibition that was organized by and associated with the Huntley collection at London Metropolitan Archives, another significant Black archival collection. I was looking at the work of Claudette Johnson in the No Color Bar exhibition, and Claudette Johnson is an artist who works in pastels and she creates really beautiful, large-scale, monolithic almost, portraits of Black women.

Kelly (24:46):

So like you do, you go on your phone to look up Claudette Johnson and find out a little bit more about her from the Googles. And there's not that much about Claudette Johnson. There's barely anything about Claudette Johnson. So I set about writing one of my first Wikipedia articles, and I wrote two others in quick succession, all about Black women artists who were active locally to me. So one of the ones I wrote was for Rita Keegan. And since we're talking about the digital, I'm going to mention that she was one of the first artists, and certainly an early Black artist who was working with computer art and photocopy art, digital art. Pearl Alcock, who as well as being exhibited at the Tate, ran a shebeen or a sort of illegal drinking den in Railton Road that was popular with the queer community in that part of Brixton.

Kelly (25:36):

Those articles were really where I started to realize the impact that one person could have on Wikipedia, which seems like a vast thing. And then through that, I got to know another editor. And editors are what we call people who contribute to Wikipedia, who make Wikipedia. And they have touched or created or significantly edited almost every article, this mysterious editor that I'm talking about. They've touched almost every article on Black British or African literature. Like hundreds, like 500 articles. And they had listed the articles that they significantly contributed to or created on what's called their user page, the space that's personal to them in the encyclopedia. And then I realized just how much impact that one person could have. I will say that this mysterious anonymous editor... I can't mention her name, otherwise she wouldn't be mysterious and anonymous, but she is an incredibly prolific editor. And she is also an incredibly significant person in the literature sector in the UK. And she edits Wikipedia for fun on the site as her hobby, as how she relaxes herself.

Kelly (26:39):

But very oftentimes when you're editing Wikipedia... And I remember creating an article for the Bristol-based playwright, Alfred Fagon, and I think maybe a year after, his monument was vandalized in Bristol and it was publicized. This was around this time last year when [inaudible 00:26:57] Colston got dashed in the harbor. In retaliation, the racists vandalized the monument to Alfred Fagon, the playwright. And obviously this was early days in the culture wars. The newspapers decided to publish big features about Alfred Fagon. And because I'd done this Wikipedia article, when somebody Googled Alfred Fagon, like we tend to do when we read about something in the newspaper, there was actually something there representing his life and his work and giving a holistic view of his life and work as well, not just one aspect of it.

Kelly (27:28):

And then Fabian, who I mentioned, encouraged me to go along to Wikimedia UK, to go along to one of the trainer sessions. And I was trained in how to train people how to edit Wikipedia, how to support people in workshops. And then I got involved as a volunteer, training for people like the British Library, the Royal Academy, the Wellcome Collection, whilst all the time working with my local library, with community groups who are wanting to learn how to edit Wikipedia.

Kelly (28:07):

There's often a conversation in the Wikipedia community about whether Wikipedians are born or are they made? For me, I see editing Wikipedia as very much an extension or an aspect of the work that I'm doing, whether it be as a guide, whether it be the work that I'm doing in supporting archives, whether it be the work that I'm not doing or that I should be doing in writing. Wikipedia is very much an extension of all of that. In training people how to edit Wikipedia, not everybody goes on to be a Wikipedia editor or contributor, and that's fine. But what is important for me is that there is an opportunity to build digital literacy for people, so they understand where information comes from, how it's created, and that they see themselves as not only knowledge consumers but knowledge producers.

Kelly (28:54):

And you can see the strength in doing that or the importance in doing that, every time in your family WhatsApp group somebody screenshots Wikipedia in order to prove a point about something, or I see somebody screenshot something that I've written on Wikipedia in order to prove a point about something. So to have the perspectives of African and African-descended people represented on what's supposed to be a representation of the knowledge of all humanity, is incredibly important.

Rudy (29:18):

What would you like to see happen in archives to make space for Black people and our histories? And in that work, how can Black communities be better engaged with archival material as well?

Kelly (29:33):

So the archive sector, like all institutions responsible for memory in the west, so museums, libraries, are reflective of our society. They're colonial. They're reflective of the systemic racism in society. So to make spaces for Black folk, whether it be as users, as staff members, means either A, fundamental reform in the archive sector, in scared quotes. There are many different types of archives, many different ways of being involved. And obviously I can talk about that a lot, so I'll try not to. So it means either reform of the sector, significant reform, or it means getting rid of the sector altogether. And I know that's what a lot of Black folk who are involved in archives advocate for, because there is no coming back from it.

Kelly (30:27):

When you look at how the history of archives in Britain and in Europe more generally, how the discipline was established and why the discipline was established, it is completely intertwined with the colonial project. The British Empire is called the first information society. One of the key ways that the British imperialists and colonizers controlled people is through information, through collecting information and description. You go to archive school, you learn about Hilary Jenkinson, who was the designer, the architect of archival education. And that is all based on the needs of the information engine of the British colonial project.

Kelly (31:10):

So where is the space for African and African-descended people in that? The space is inherently colonial. So I think that is a useful thing to remind ourselves when we're thinking about this question. I don't have any particular expectations around the archive sector, which is why it's really important that we create ways of archiving that are independent to the UK archive sector, that we can self-determine, that we can apply different ways of working. Because to apply the standards and the practice of the archive sector is to apply colonial and racist standards and practice.

Kelly (31:59):

And again, if you're talking about where is the space, because where are the archives of Black people, or people racialized as Black, represented in British archives? Yeah, of course. And as I mentioned, they're often the records in the archives that are undervalued, that are restricted, that have been destroyed, that have been ignored. And they're the archives of surveillance. One of the things that really gets on my nerves is every time the National Archives talks about its records around the Black Power movement, they barely mention... I think they've been doing a little better in the past year. Surprise, surprise. But they barely mention that these are the surveillance records created by the police. And a similar thing, not only with the Black Power movement in the 1960s, but also most of the records that they have around whether it be nightclubs throughout the 20th century, whether it be queer people throughout the 20th century, wherever it'd be the records of enslavement itself, these are the records that were used to subjugate, control and oppress people.

Kelly (32:53):

And yeah, I think those conversations are happening on an academic level, but I don't think on a community level there is an awareness that these are the records that are represented in the British archive sector. So this is another reason why I prefer to use the term "independent archives" as opposed to "community archives". I think in the archive sector, "community archives" is seen as not professional, or unprofessional actually, or is seen as something that is less significant or more disposable than the professional archive sector. So I prefer to use the term "independent archives" to describe the variety of different organizations, and we discussed a few, that are creating archives, involved in preserving archival records, but that are not part of the broader system of local authority archives or state archives like the National Archives.

Kelly (33:42):

Is there a way that Black communities can be better engaged with archive materials? To be honest, there have been a variety of attempts to get more involvement from "the community", in inverted commas, and to share the authority that archives have. And as far as I can tell, none of them have done anything particularly significant, mostly because they've been undermined in various stages, for a variety of different reasons or in a variety of different ways.

Kelly (34:08):

And again, I'm probably phrasing your question poorly. The best way is for the archives to rescind power. That's the only thing that they're going to do. And is an institution going to rescind power? I don't think it is, but I'm super cynical. So I don't have a lot of hope in the archive sector. So for me, rather than, "How can archives create space for whatever?", it's more, "How do our communities demand that they rescind power?" So, yes, that I think would be a more effective means of creating change right now. Or the revolution still might come. You never know.

Tania (34:49):

I think that's a really lovely place to round up.

Rudy (34:54):

Yeah. Thank you so much. This has just been incredible. I feel like we could just listen to you chat all day.

Kelly (35:00):

Yeah. Like I said, I talk a lot. So you know what I mean?

Tania (35:05):

But this has been a really, really useful conversation. And even just with the names that you've given us as well, hopefully that allows people to go and do further research and learn more about the people and the places and spaces that you've mentioned.